Savant. Rockstar. Gifted genius. Many of the ways we talk about creative work only capture the brilliance of a single individual. But creativity also thrives on diversity, tension, sharing, and collaboration. Two (or more) creative people can leverage these benefits if they play well together. Cooper’s pair-design practice matured over more than a decade, and continues to evolve as we grow, form new pairs, and learn from each other every day. While no magic formula exists, all of our most successful partnerships to date share remarkably similar characteristics…

Foundation

We play by the same rules

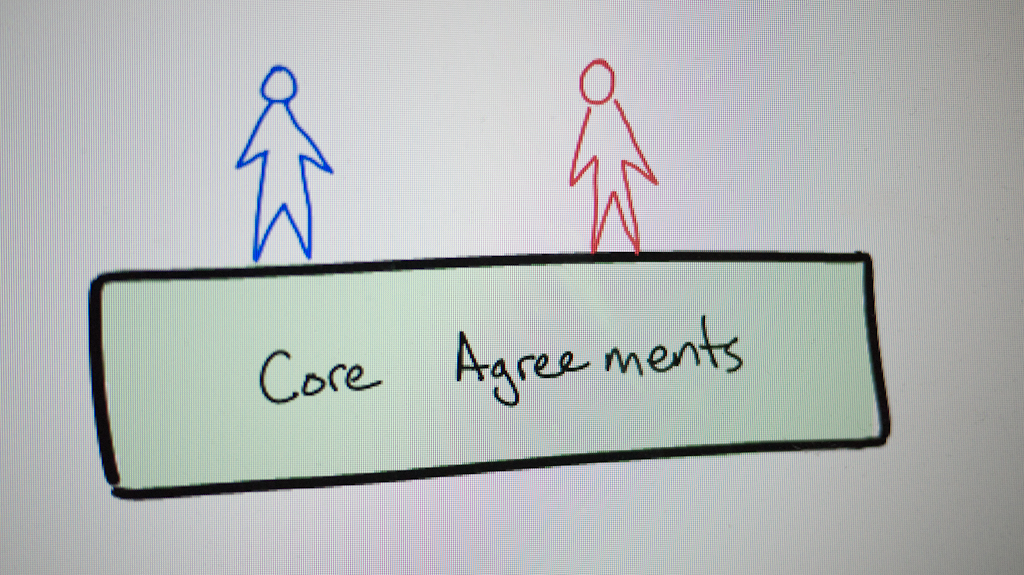

There’s many different ways people could work together, but when everyone’s playing the same game (and has a shared understanding of the ground rules), things flow more easily. The freedom to make up the rules as you go, according to your own whim creates chaotic, unstable, unpredictable systems. It’s hard to get work done when the basics are continually questioned.

David Bornstein a journalist who studies social innovation, recently described play in the New York times: “Play requires the acquisition of a complex set of skills. It’s not just about exercising or letting off steam. It’s about making agreements with others as equals, stepping into an imagined structure, and accepting that structure even when things don’t go your way.”

At Cooper we’ve got a loose set of agreements which give structural support for playing and producing together. We’re all consultants, doing user-centered design, following an archetypal process (adapted to a given project’s constraints), and we maintain specific roles for working together. These serve as the agreed upon structure or rules of the game.

How it’s played is left to the players. We value lots of autonomy within big boundaries. Every team settles on their own ways of working together for day-to-day project work. It’s as informal as a sketch of a calendar and a quick conversation around expectations. We make explicit what we need to get out of our time together, and what we’ll get done in our time apart. Everyone shows up on time, and ready to work. A quick goal-setting chat gives focus and clarity to design meetings. Starting on the same page gives permission to time-box discussions, and park unresolved questions. In meetings we’re present, actively contributing, and moving the project forward. Shared agreement about the game we’re playing removes stress around participation and supports a more trusting relationship.

We make the most of differences

We deeply value differences. The articulation of our interaction design roles (synthesiser or generator) came from noticing and formalizing specific differences in design approach and skills. A solo designer usually is forced to perform this work alone, serially alternating between generating design and stepping back to synthesize it. With a pair we do it concurrently: when the generator is focused on articulating the details of the concept, the synthesiser is going the other direction, stepping back to see how the idea fits into the big picture. Each pushes the idea differently and we end up with more effective collaboration resulting in better, more thought-out design. By focusing on different skills we support and balance our partner, instead of competing at the same tasks. Our partnerships promote a diversity of thinking, perspective, and knowledge.

The division of work and responsibilities is fair and equal. It supports differences without generating unnecessary conflict. This doesn’t mean we’re conflict avoidant. Part of the value in difference comes from the natural tensions inherent in the differing points of view. Diversity encourages questions and healthy debate. We occasionally face substantial and sometimes uncomfortable disagreements. This pressure and heat acts as a crucible, helping separate the essential from the trivial, the promising from the dead-ends. Complementary roles and responsibilities encourages and gives permission to challenge while structuring the tensions for the most productive results.

Having a specific role and responsibilities frees your creativity. You don’t hold back as much. You devote yourself completely to your “specialization”. You depend on your partner to bring balance. This pairing of “opposites” generates more fruitful disagreements and enables deeper synthesis of ideas. When hiring people we pay particular attention to their strengths and natural tendencies looking for how they match to our roles. No individual fits perfectly into the box, but we find certain tendencies (such as thinking visually or with words) to be strong predictors of affinity for a given role.

We do our homework

We set ourselves up for success by understanding the domain, problem and users before we jump to solutions. There’s little benefit in putting two uninformed designers on a project; you can’t get more when you multiply by zero. The more preparation we have, the more confidence we’ll bring to solving the problem. Creative partners without sufficient knowledge foundation must rely on their opinions and theory. This increases the challenge of working with someone else and may create unfruitful conflict between partners.

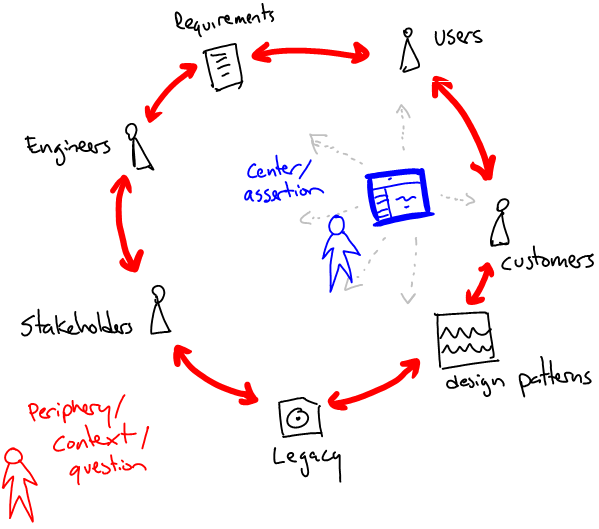

Without adequate preparation teams struggle at keeping momentum, we don’t achieve real flow. Research arms our teams with more objective information, increasing out skill and ability to work in complex systems. We reach flow with our partner when we have the right information to meet the challenge. We try to ensure both partners have a working understanding of domain and the problems we’re working to solve. If one team member has more experience in a domain, we make the effort to get their partner up to speed. Everyone needs enough grounding in the domain and familiarity with the users and business needs to confidently, smoothly work toward solutions.

We use the right tools for the job

If our pairs were to use opinions and desires to drive design there’d be lots of opportunity for unresolvable conflict. We take a lot of the personal opinion out the equation by using the right tools at the right time.

- Research instead of speculation

- Personas instead of personal preference

- Scenarios instead of “what if…?” (edge cases)

- Sketches instead of pixels (for early concepts)

- Pixels instead of sketches (for refined design)

- Patterns instead of isolated solutions

We limit distractions

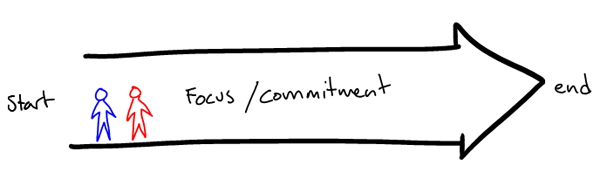

Too many distractions and the core project suffers. There’s a significant overhead in changing gears from one project to another. Designers can perform good work on more than one project at a time, but when you’ve got a pair of designers both juggling different priorities it adds to the stress and limits the benefits.

We structure projects for one team, one project. It’s more enjoyable, and we get much more out of our partnerships. Quality and productivity rise, stress and conflict fall. With no other distractions, you can give deep commitment and focus. You dive in with everything you have – success is yours to lose.

Guiding principles

We don’t design alone

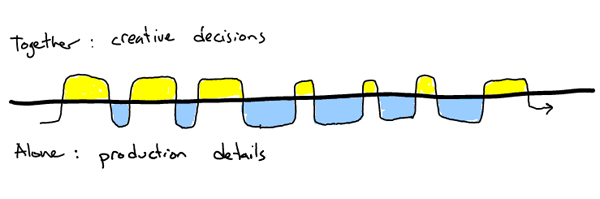

In many creative endeavors collaboration takes the form of designing alone at your desk and then reviewing your thinking with someone else. This approach makes your partner an editor rather than collaborator. For us, collaboration means solving the big design questions with our partner. Co-ownership of design is critical. Both designers must understand and contribute to design rationale. Throughout the project we alternate between collaborative design meetings and “alone time”.

Earlier in projects we spend the majority of time together. As a project advances we increase alone time for working through the the pixel and pattern details. Working through the details inevitably brings up new issues or questions that were not considered before. When this happens we jump back into a design meeting and figure it out together. We don’t make unilateral substantive changes in direction without grabbing our partner.

We externalize our thinking

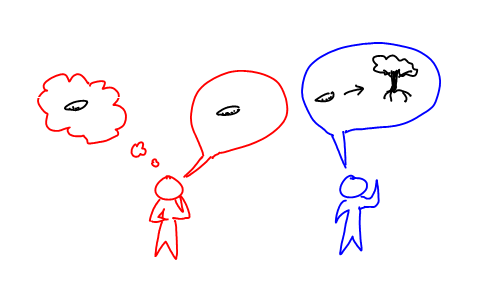

Many designers learn that if you work it all out in your head, you can anticipate and mentally address the more obvious shortcomings to your idea. The more thought-out, the more coherent and credible, the less revisions and reformulation. This works well for solo practice, but it breaks when you try it as a pair. Doing all the work in your head shuts your partner out. They can’t add on, poke at, or improve upon something that’s kept in your head.

Co-creation needs externalized material. Sharing the fuzzy, early, raw concept gives your partner material to work with, to respond to and evolve. Externalizing ideas allows for closer collaboration, earlier input, and deeper thought partnership. This is true when generating and proposing ideas, and equally important for synthesising and evolving concepts. Both partners must work at sharing early unfiltered thinking. It takes time to get comfortable working this way. It means trusting your partner. Trust is earned by creating a safe space for sharing and growing ideas. This was of working really leverages the power of two. Two perspectives, two minds, two creative processes, working with good seed ideas results in quicker, better, deeper insights.

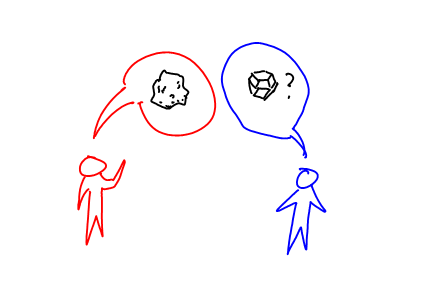

We presume value, even when it’s not obvious

First expressions of ideas rarely achieve elegance, clarity or completeness. A negative reaction to a poorly expressed idea usually feels justified, but it rarely helps your partner make their idea better. Just because the first expression stumbles, doesn’t mean there isn’t a good idea somewhere in there. Your trusted thought partner’s contribution is valuable, even if its expression is poor. Unearthing the core idea or objection always leads to better insight.

This only works when partners make safe space for sharing still-forming ideas. Each partner works hard to understand the intent, not simply the expression. Once it’s been proposed you can respond, refine, improve or ask for additional clarity. Working this way helps remove self-censorship and premature editing; allowing better flow, more sharing and deeper trust. We still eliminate lots of ideas, but not without some amount of early consideration.

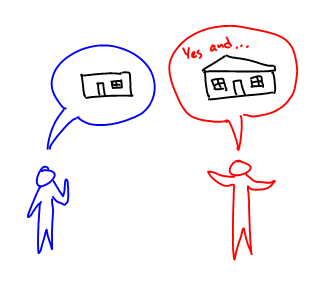

We build, instead of blocking

Shooting down ideas or feedback quickly kills momentum and goodwill in a partnership. In design meetings you keep momentum by working with, and trying to improve upon, the contributions of your partner. You push the proposed idea further by adding to it, improving it by clarifying nuances, building upon it as a hypothesis. Sure there are times when what your partner says seems a bit crazy, when the direction may seem like a waste of time. But simply shooting them down rarely moves the design forward, and frequently it completely stalls the creative flow.

Building also means seeking and receiving input. When your idea stinks, someone needs to point it out. You can’t evolve the idea when you dismiss or ignore feedback. Shutting your partner down prevents them from collaborating to improve the work. When responding to proposed solutions negativity doesn’t move the idea forward. You improve it by adding, augmenting or adjusting a concept so that it’s better meeting project or user goals. This keeps the ball rolling, and we feel like we’re on the same team.

Sometimes we can’t come to an agreement (see Time-boxing disagreements below). We accept that currently there’s no mutually satisfying solution. We’ll make a deliberate choice in direction, remain tentative in our commitment to it, and move on to the next problem. Often working on the rest of the system adds clarity. We may find more agreement once we see how the rest of the problems resolve.

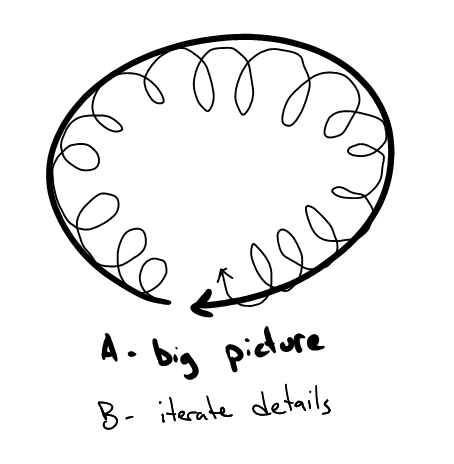

We seek progress, not perfection

As a design consultancy we work with lean schedules and high expectations. We strive to deliver the best possible work in the time allotted. We aim for killer ideas, but these rarely pop out on the first try. We get there through rapid iteration. You can waste lots of time banging your heads together trying to come up with perfect designs, but no amount of effort work everything out. When your client or your users see they’ll have feedback. This will mean revisiting decisions, even if you thought they were “perfect” or “done”. We sketch out the big areas first, making sure the whole system works. Then we meet with clients, we show it to users. Things change and we roll with it. We make it better by incorporating feedback and working deeper into the details and nuances in progressive iterations.

We cover vast amounts of territory in short amounts of time by working on the big picture first. We count on following with later refinements to figure out the details. This approach also brings coherence and consistency to our designs. The churn pursuing a perfect solution kills more than momentum; if we spin for too long it drains the design process of enthusiasm, joy, and inspiration. When we get stuck we park it and make a plan to revisit it later.

We leave our egos at the door

Differences could lead to unproductive acrimonious disagreement; at their worst breaking teams apart, stalling progress or draining enthusiasm. How do we make disagreements productive instead of damaging? We work at setting aside our desire to be right and focus instead on trying to understanding what’s making our partner uncomfortable. When your trusted, committed, invested partner can’t agree with what you’re suggesting it’s lacking something critical. We look at our partner’s questions as earnest testing of the idea rather than hostile personal attacks.

This doesn’t mean it’s all rainbows and unicorns. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable giving or getting feedback. Even when your partner means well, it’s hard to hear your idea’s not working. Disagreeing with your partner’s strongly held idea takes courage. We work at putting our egos aside because we know that figuring out what’s not working it will almost certainly make the design better. We’re not striving for consensus, however we recognize that if your partner’s not convinced, it’s in the interest of a better design to unpack the objection. Often addressing the concern leads to innovative new solutions, beyond what either partner initially brought to the problem.

Practice

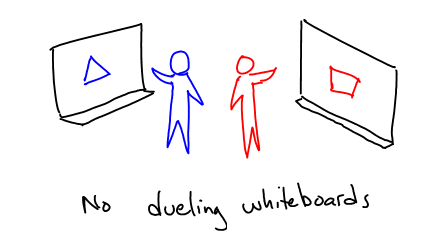

We limit direct competition

While polarity can be productive, prolonged direct competition with your design partner isn’t. It’s easy to fall into dynamics where the debate moves away from designing the right solution to choosing between competing ideas. This frame is lousy. Design bake-offs don’t often lead to better solutions, and they unnecessarily create winners and losers. We find that sticking to specific roles (synthesiser or generator) helps decrease competition. It’s less important that role assignments are rigid and eternal, but really critical that in a given creative meeting, we both aren’t trying to play the same role.

Early on we take a divergent approach where we get as many different approaches on the table as we can. Everyone generates. Then we evaluate the results, looking for what’s strong and what’s weak about every idea. After this we let the generator lead the charge. In any given meeting roles may temporarily switch for a time and then revert back. The goal isn’t strict adherence, but to limit direct and unproductive competition.

We refer to this as “no dueling whiteboards” or “one pen, one idea”. While your partner uses the “pen” to propose a design, you focus on understanding and responding. While your partner evaluates your “idea” give them a chance to understand and improve it; stay with the idea, until they are ready to move on too. When synthing, trust that your partner’s doing their best to come up with great concepts and solutions. When the idea shows promise focus on improving the proposed solution. When it’s not working, show where and help work toward something that does. When generating, trust your partner to look out out for bad ideas. They keep you honest and track the big picture. You rely on one another. It’s a balancing game, working to keep equality. You don’t want to give in or give up, and you don’t want to steam-roll or win. Winning only happens when both partners bring their best game, keep up their end the deal, and rely on one another for balance.

We time box disagreements

Different points of view can lead to extremely fruitful insights. They may also lead to divergent ideas or conflicting solutions. We value the diversity of perspectives, but find diminishing returns when disagreement can’t be quickly resolved.

There’s times when two smart people can’t figure out a way to agree. We place place limits with a loosely applied 15 minute rule. If we come to a stalemate we grab a neutral third party. We explain who and what goals we are trying to serve and what ideas are on the table. We aren’t looking for a referee, but rather a less biased perspective, someone who can help us step back and see the context for the disagreement. We want insight which helps us let go and bring a fresh approach which subsumes the initial conflict.

We seek and give feedback

Festering issues never serve a creative partnership. We strive to set a culture where everyone feels empowered to speak up when something’s not working. In a perfect world, misunderstandings, resentments, assumptions and hurt feelings would never enter design relationships, but sometimes rear their ugly heads. If something doesn’t feel right it’s important that partners find a way to work it out. We believe in improving working relationships through constructive feedback and regular check-ins. It’s hard work and can be uncomfortable at first, but with experience trust builds and communication improves. You may never develop a long lasting friendship (though many friendships do occur) but with practice you can build amazing working partnership.

Putting it all together

Developing trust takes time

All newly formed teams must work at joining forces. Your partner brings a new style, idiosyncratic quirks and habits. Integrating each partner’s perspectives, experience, skills and methods takes time and effort. Early on meetings may feel strained, communication a bit awkward or clumsy. You can’t help stepping on your partner’s feet while figuring out how to dance together. This upfront effort is worth it because you can reach amazing levels of trust. Once you get over this initial learning period the relationship gets easier.

Trust comes through seeing that your partner plays by the same rules, from sharing ideas which are improved upon, through experiencing value in a difference of opinion, by responding to the idea not the person, in showing up on time ready to work, in meeting expectations and honoring agreements.

We work in challenging ambiguous creative space. Developing a foundation of trust provides structural strength for productive work in chaotic systems . It allows for deep thought partnership, understanding, respect and trust in the other’s commitment. In great partnerships the overhead of meta-relationship management falls away. You look forward to designing together, you appreciate that someone’s always got your back. You become close, you take on the challenges together, you look for ways to leverage your partner’s contributions. It’s usually fun, it’s sometimes challenging, but once your relationship matures you rarely want to go back to solo design work.